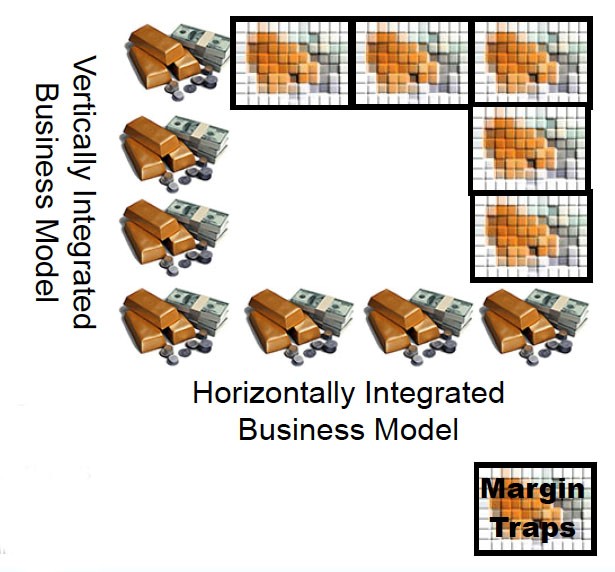

Of the three business integration models: Horizontal, Vertical, and Matrix, matrix is the most powerful but also the most difficult to execute.

The matrix integration model is new, so don’t be surprised if you haven’t heard it before. I named it to put a label on the business structure Samsung has built. With it, Samsung has accomplished a major innovation in business infrastructure models. Before we get to that, a few definitional notes are in order. The horizontal and vertical integrations are well known and generally provide a better defensive position than being in a single market.

The horizontally integrated business model is perhaps the oldest known. It is a method where your business focuses on a single customer class and moves horizontally outward along a single link in the supply chain to provide complementary products to that customer class. Grocery and Department Stores are probably the earliest models in this class, which evolved out of street markets in the 19th century.

Customers come to the horizontal company for the convenience of one-stop shopping and the brand promise of consistent quality and delivery. In the era of mail order, Sears & Roebuck rose by being a brand you could trust. Suppliers hand over sales responsibility to the horizontal model because that’s where the customers are and it allows them to focus on making their product, while outsourcing the task of selling. The horizontally integrated company benefits because moving horizontally unlocks margins trapped in competitive suppliers, which are pushed down a tier in the supply chain.

Applied Materials, KLA-Tencor, and Tokyo Electron are good examples of horizontally integrated tech companies. Both were built on the basis of a good product and then branched out horizontally with more solutions, as they became brands you could trust. Like someone in the nineteenth-century West ordering from a distant Sears, the semiconductor industry encountered the same trust issues as it went global in the nineties. Hence the rise of Applied, KT, TEL, and others.

Mike Splinter took the horizontal model even further at Applied by using the company’s core technology to expand horizontally into new customer bases, such as Solar PV. This is risky, because a company needs to build a new sales and marketing front-end structured to build the deep customer relationships for sustainable business. The technology is the easy part. The risk is that either you fail in the new market or that success comes at the cost of failure in your existing market. So, you only have a one-in-three probability of success. Mike managed to accomplish the move without dropping one for the other. One could argue that Applied had already moved horizontally outside to displays, but there was a difference: it was Applied’s same customers who had shifted over to the display sides of their business to solve defect issues. They then pulled Applied in, making it a tactical, not strategic, move. In contrast, the move to Solar PV was very strategic and required Applied to build entirely new relationships.

But while the horizontal model unlocks margin traps to each side, it leaves traps vertically above and below in the supply chain. The advantage of this is that customers and suppliers will not see the horizontal company as a competitive threat. While they could see it as a threat to margins, the benefits and efficiencies gained by working with a horizontally organized company typically outweigh any threat. The latter is because the primary profit advantage of the horizontal company is in pricing and negotiation. If one product line is threatened by a competitor or lower demand the horizontally organized company can respond with lower prices, using profits from stronger products to offset the variance. It can also do the reverse when conditions are the opposite. It uses open horizontal lines to strengthen weak points along the line, giving it a strong unified front. As a result, horizontal competitors are typically known as ruthless negotiators, because of their monopsonistic position. Wal-Mart is a primary example of this.

The vertically integrated business model is more modern, evolving in the early twentieth century, most notably at the Ford Motor Company. At its height of vertical integration Ford processed sand into windshield glass and iron ore into steel. The classic example of vertical integration in technology is IBM, which ruled the computing market for most of the twentieth century. With it, vertical margin traps are eliminated, but horizontal ones remain with competitors. The vertically integrated company competes horizontally. For it, strategic and tactical advantage in the product are critical core strengths. It is price agnostic up and down the supply chain, since there are no vertical margin traps.

Customers come to the vertical company for its expertise and consistency of service and supply. In the era of the big mainframe, computers were expensive corporate investments in which companies had little internal experience. Switching often resulted in what was called a ‘forklift upgrade,’ because it took a forklift to remove the old computer and put in the new one. These were complex and painful transitions. IBM, with its control of the supply chain, could be trusted to make a computer transition as risk free as possible. Moreover, IBM could be trusted to service it quickly and always have spares readily available so capital was not trapped with lots of downtime. They were so trusted that it became common to hear the phrase, “nobody ever got fired for buying an IBM.” More recently, IBM reinvented itself by transitioning the vertical model to the IT services sector.

The semiconductor equipment business was once highly integrated vertically and even part of the semiconductor industry itself. It did not stay that way because few equipment companies had the unit volumes to get to the economies of scale needed for an efficient vertical model. In the case of the semiconductor industry, even design and manufacturing broke away into that fabless and foundry sectors.

The Matrix Integration Business Model combines both vertical and horizontal integration vectors. It pushes the margin traps to the outside of its vectors, forming strong defensive fronts that become like fortress walls.

The advantage of the Matrix Integration Business Model is that it can use interior lines of profit direction to focus resources on the hottest areas of competition and/or opportunity. Product development and partnering are the most critical core strengths for this model. The reason is that competitors, customers, and suppliers will all see you as a competitive threat. So you need a strong core technical strength and the partnering skills to convince both customers and suppliers that while you compete with them, it’s worth their while – and even necessary – to partner with you.

Samsung developed this model by using their IC core manufacturing strength to focus product development outward. They were once Nokia’s largest subcontractor for cell phone manufacturing. When Nokia abandoned them, they had developed the ability to successfully enter the handset business at the low end. They then levered this entry point all the way to smartphones. Working with Apple to supply flash and foundry ICs, they were able to respond to the emergent tablet market far faster than other electronics companies.

At this writing, two-fifths of Samsung’s workforce is workforce dedicated to R&D. They have extremely high RoR (Return on Research), leveraging both internal and external innovation sources. By 2010, they were second only to IBM in patents registered that year.

The Matrix Integration Business Model is still too new to know if it will stand the test of time. Most never thought Samsung would be able to pull it off in the first place because of the unwritten 20th century rule that you never compete with your customer. But this is the 21st century and the rules of partnering are far more complex and political. It’s very much like renaissance Italy, in which Machiavellian principles and relationships are the rule of the day. If the world changes, Samsung could find itself against a strategic alliance much like Napoleon did, as the fragmented royalties of the continent were aligned by Britain against him.

By G Dan Hutcheson Copyright © All rights reserved.